Cover Story

Spring 2010, VOL.10 NO.1 |

A Challenge that Builds Confidence and Commitment

Welcome to ENES 100, the Clark School’s Introduction to Engineering Design course. Every freshman takes it—609 in

the 2009-2010 academic year, in a class size averaging 40

students—and it is an experience they will all remember.

The semester-long class is taught by carefully selected Keystone professors and involves both formal lectures and presentations by outside experts on subjects such as product development, ethics, globalization and modern engineering trends. But most students think of it as “the hovercraft course” because working in teams to design, build and fly a hovercraft consumes their every waking hour in the second half of the semester.

At the test course, the Team Friendship hovercraft rises on a jet of fan-generated air, but something goes awry. The vehicle veers sharply to the left and crashes into a wall, coming to a dead stop.

“Maybe it’s a weight distribution problem.”

“Could be it’s a low battery …”

“It’s the servo mechanism…I think we need to reprogram.”

“It’s a propulsion problem…”

“Our fans are not turning off fast enough. Maybe they’re

overcorrecting…”

|

Disappointing? Yes. Disasterous? No. Students must deal with failure, learn from it, and find the confidence to try new solutions. Team Friendship is eager to determine what went wrong. The chance to work with classmates to build a functioning vehicle, they say, has engaged them more than any other assignment they have encountered on campus.

“Hands-on design experience can be highly motivating, and it can give students a reason to persist in engineering and make a deeper commitment to their classwork,” says Keystone faculty member Sheryl Ehrman, associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and a strong advocate for ENES 100.

“Some bright underachievers don’t really connect with engineering until they have a chance to get in the lab and create something.”

Ehrman recalls a similar experience as an undergraduate in California. “It sometimes seemed in the first two years that my engineering school was trying to beat the creativity out of me and my classmates. Not until we got to our more advanced coursework and labs did we have the chance to experience the fun and the challenge of engineering,” she explains. This is a sentiment many engineers, including some Clark School alumni, might echo. |

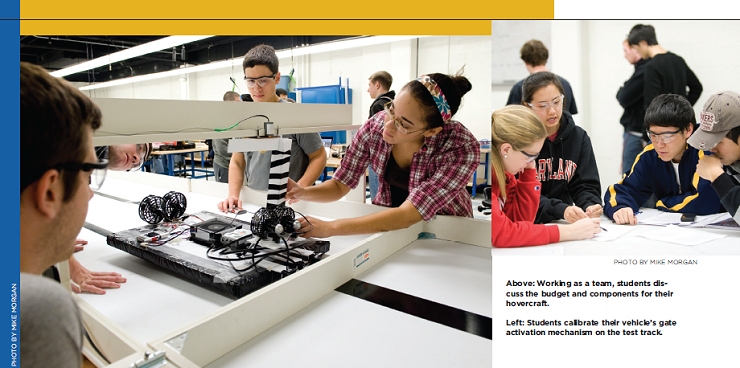

She draws on her own experience to make ENES 100 as challenging as possible for students. “We build challenges into the hovercraft assignment that students must overcome,” she says. “The fans, sensors and microprocessors have to work together. Most of the students have never confronted problems like this. It’s exciting for them.” Each year, the faculty members look for new ways—like the gate-opening requirement—to add interest and challenge. They have also created a hovercraft display in the J.M. Patterson Building to show different designs over the years and build students’ pride in their work.

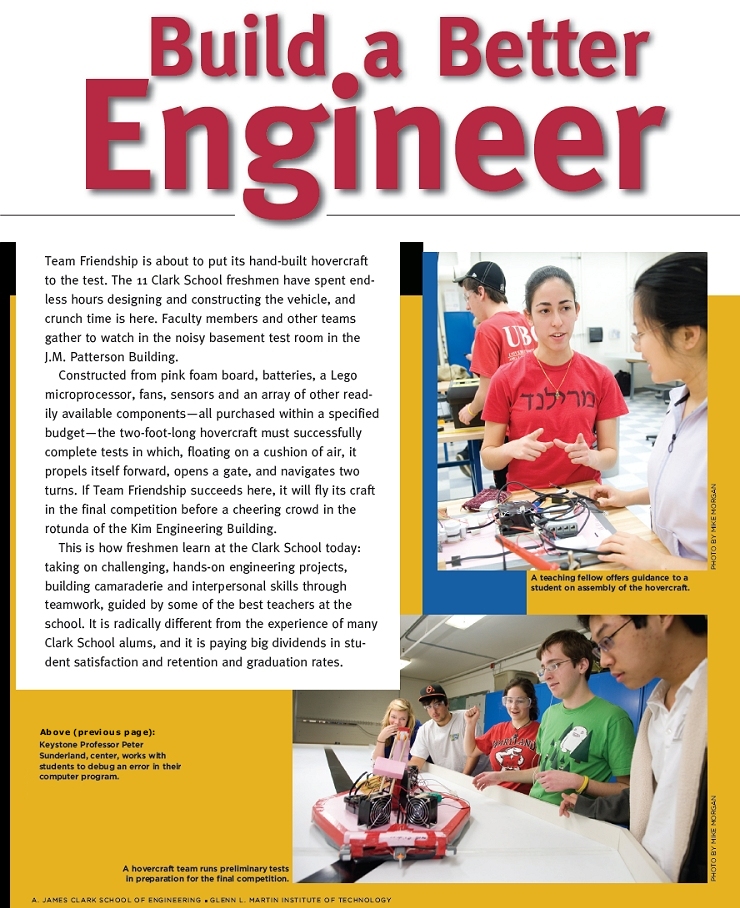

Learning How Engineering Gets Done

For Amy Cheng, B.S. ’13, a potential bioengineering major, ENES 100 has helped her view engineering as the sum of many contributions. “I have been excited to see how the design process works, how different subgroups undertake different tasks, and how all these efforts come together.”

With its product development orientation, ENES 100 is designed to introduce students to the kinds of on-the-job demands professional engineers must meet. The course incorporates seven product-development milestones, and teams must strictly adhere to deadlines and schedules.

|

|

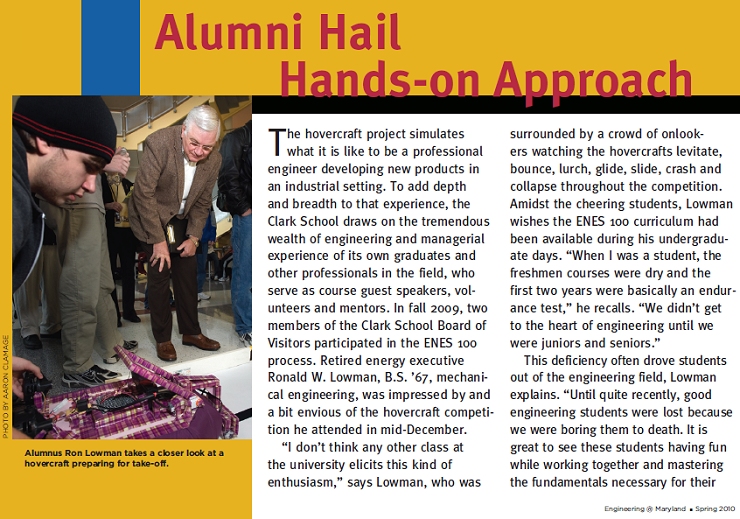

Photo by Aaron Clamage

Recognizing the importance of strong communication skills for engineers, the Clark School has incorporated formal written and oral team presentations into the course. Regardless of their success in the competition, the teams are again on equal footing as they make their first formal presentations as aspiring engineers. Dressed in business attire, the students detail their successes and failures before a faculty panel and provide a hefty packet that documents all of their efforts.

ENES 100 students develop real-world attitudes through their baptism under fire. “You have to let go of your perfectionism,” adds Jeff Sze, B.S. ’13, who is interested in the clean energy field. “I used to think solutions could be perfect. I see now that engineering in the real world is about approximations.”

Amanda Heyes, B.S. ’13, who is still deciding what area of engineering to pursue, raises another crucial point. “The course teaches time management,” she says. “You have to design the components simultaneously and you have to leave enough time to integrate them. All of the deadlines come up much faster than you expect.”

And a crisis can occur at any time. One day before the deadline to qualify for the competition, Heyes’s team encountered a problem. “Our battery caught fire when we were testing it. Our circuits were fried,” Heyes describes. The team spent most of the day struggling to integrate the new battery into the hovercraft’s propulsion system, and their efforts paid off. “Coming down to the wire, we got really good at teamwork, which helped us make it into the competition,” she reports. By the end of the fall semester, 32 of the 48 hovercraft teams managed to qualify for the final competition.

Building Clark School Engineers

The challenge—and the fun—of ENES 100 help to attract great students to the Clark School. When they take the class, students learn firsthand the level of commitment required to succeed in the

|

|

undergraduate program

“Students are here because they want to be. It’s amazing how dedicated they are,” notes Keystone Instructor Kevin Calabro, who spends countless hours with the students during the vehicle design, construction and testing phases.

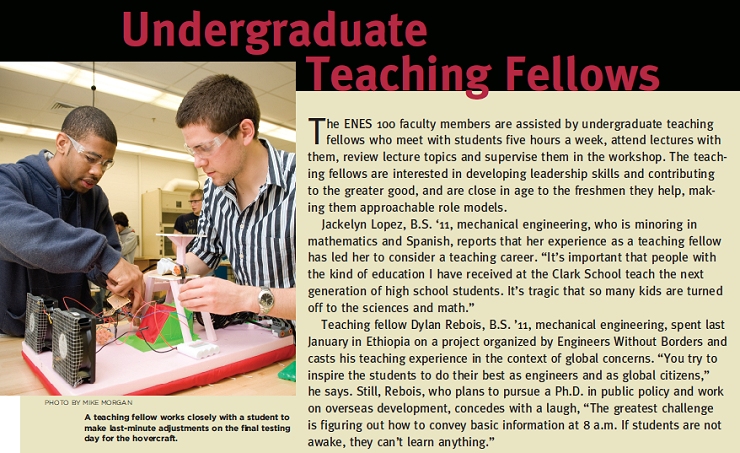

Many go on to participate in national and international competitions. Clark School students won first place among U.S. teams in the 2007 Department of Energy Solar Decathlon and are preparing to compete in the 2011 contest (see related story, p. 18). They have garnered top honors in numerous NASA competitions, placed first in the American Helicopter Society Student Design Competition nine out of 10 years, and have established a winning record in the national Biomedical Ethics Essay Contest. Others pursue engineering service activities, such as water and energy projects sponsored by Engineers Without Borders in impoverished communities around the world. And all students can build on their ENES 100 experience through advanced capstone design courses and professional internships at the many federal agencies and corporations in the Washington, D.C., area.

Proof in Numbers

Former Clark School Dean Nariman Farvardin established the current format of ENES 100, together with Keystone: the Academy of Distinguished Professors, in 2006. Keystone provides support for top professors to teach the most elementary engineering courses, ensuring that new students have an excellent academic |

experience early on, get an overview of the engineering profession, learn the importance of math and science to their success, and develop good habits in homework, exams and written assignments.

Such high-quality courses improve student retention and graduation rates. William Fourney, Clark School associate dean, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, and lead Keystone professor, attests to the success of ENES 100. By tracking and collating various data sets, Fourney has correlated rising retention rates at the Clark School with the school’s educational innovations. His research demonstrates that since the inception of the first design-based freshman engineering courses in 1992, retention rates have increased by double digits and the percentage of students graduating in four years has risen dramatically. Following the introduction of ENES 100 in its current form, nearly 75 percent of students who entered the Clark School during the 2007-08 academic year remain enrolled two years later.

When ENES 100 debuted, Fourney and other faculty were more focused on improving the quality of the classroom experience than boosting retention rates. “We thought freshmen and sophomores should have access to the best teachers, those who earn the teaching prizes,” he says. “There have been times when

I looked at classes of freshmen and asked myself ‘Will they ever be engineers?’” While Fourney admits it takes extra effort to get students over the freshmen hurdle, the results are worth it. “By the time they are seniors, they are performing at the highest levels,” he adds.

Fourney recognizes that especially dedicated and passionate instructors are needed to teach freshmen and sophomores. For that reason, all Keystone faculty members, including the dozen who teach ENES 100, are rigorously selected by the Clark School.

|

|

The Keystone Professor: Key to Success

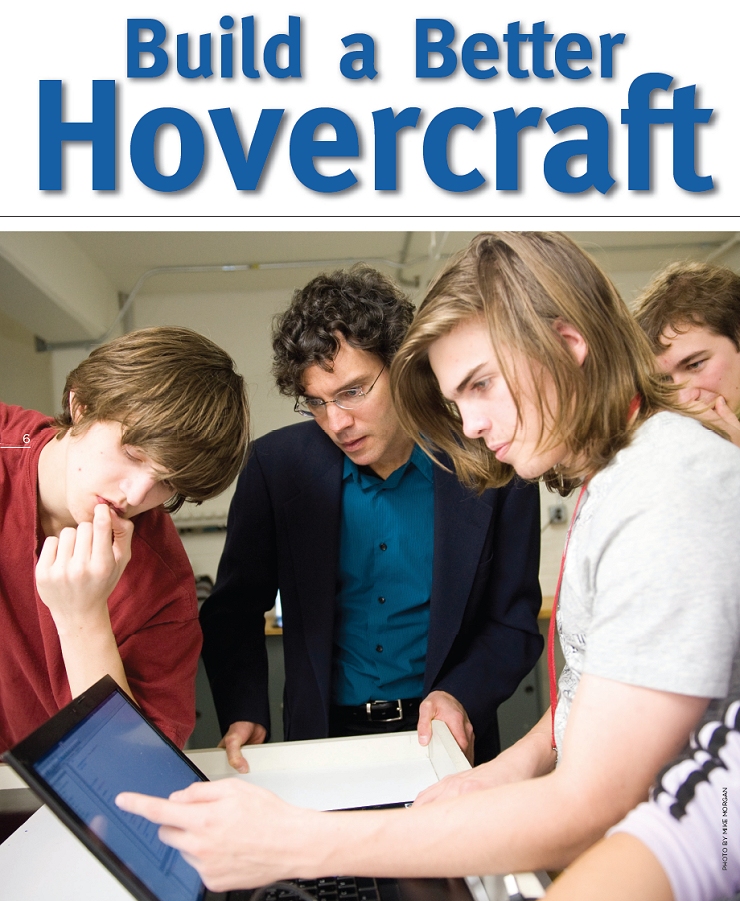

Peter Sunderland, Keystone faculty member and professor of fire protection engineering, is one of the talented teachers who make the course a success. Sunderland describes how the class addresses the academic talents of today’s students while helping to ease their transition into the Clark School. “These students are 17- and 18-year-olds, right out of high school. On this big campus, they need a smaller group to relate to,” explains Sunderland. “ENES 100, with just 40 people in a class, gives them a chance to get to know one another and their instructors.”

ENES student Justin Huang, B.S. ’13, who hopes to become a researcher, agrees. He confirms that working as part of a team in a small class helped him overcome feelings of isolation he experienced in the first weeks and months as a freshman. He also appreciates the chance to roll up his sleeves on a project. “I see all this tinkering and trial and error as the entry point to my future career as an engineer,” Huang explains.

|

Sunderland believes working in teams “where there are lots of right answers,” provides students with “a better idea of what the engineering profession is really about.”

ENES faculty members and instructors also work as a team, following the same schedule, delivering the same six basic science lectures and assigning the same homework.

The lectures, which cover the scientific concepts students use to design and build the hovercraft, include such topics as fluid dynamics, electronics, microprocessors and sensors, and hovercraft dynamics and controls. A final lecture focuses on team dynamics.

The team approach has benefits for instructors as well, Sunderland says. “Usually when you teach, you don’t have a chance to discuss the best ways to get certain material across to students,” he says. “With ENES 100, the faculty and instructors meet every two weeks to brainstorm about best practices.” |

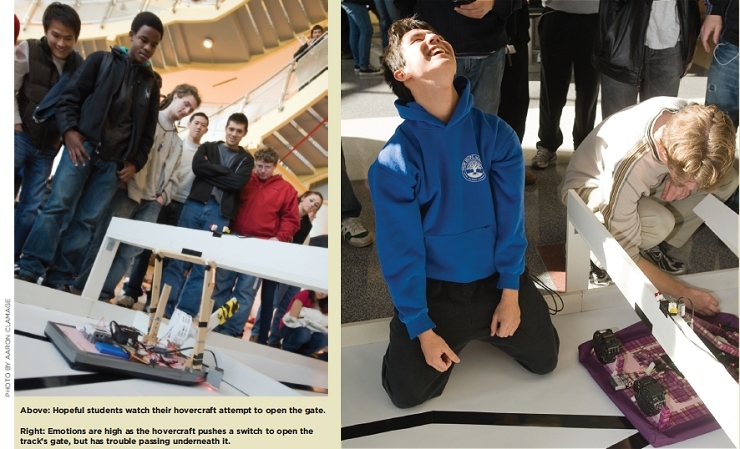

Team Friendship and the Final Competition

The hovercraft competition is underway in the rotunda of the Jeong H. Kim Engineering Building on a bright, sunny day; a bit too bright in fact. The abundance of sunshine confuses light sensors on many of the vehicles. Team Friendship’s hovercraft hits the wall on its first trial. Bound by duct tape and sheer enthusiasm, the vehicle somehow makes it to the Final Four. Now, on its last run, the craft levitates, then proceeds awkwardly down the track toward the gate. Its robotic arm, using springs from a ballpoint pen, rises and hits the switch to open the gate.

The hovercraft inches forward and navigates under the gate. “Oh my God! It worked,” someone shouts, and the Kim Building rotunda fills with applause.

|

|

|

|